The Struggle in Washington

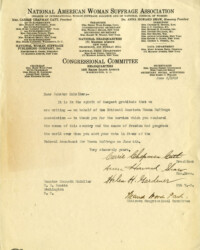

“Thank you for the service which you rendered the women of this country and the cause of freedom and progress the world over when you cast your vote in favor of the Federal Amendment for Woman Suffrage on June 4th.”

— Carrie Chapman Catt, et al. from Letter Thanking Senator for Voting for 19th Amendment.

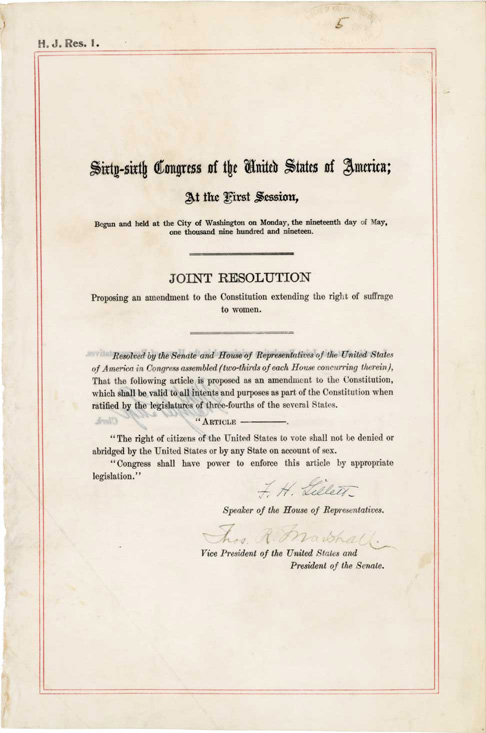

CONGRESS PASSES THE NINETEENTH AMENDMENT

Introduced in the United States Congress in 1878, the proposal that eventually became known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment (and today, the Nineteenth Amendment) quickly disappeared into the recesses of a Senate committee. For the next four decades, it lingered neglected with little to no action taken on the measure in Congress.

“We have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

Woodrow Wilson, Address to the Senate on the Nineteenth Amendment.

The proposed amendment attempted to follow the pattern blazed by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, all of which conferred previously unrecognized rights upon African Americans. The struggle for the Nineteenth Amendment followed the failure of a legal battle that went all the way to the Supreme Court over whether the Fourteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote.

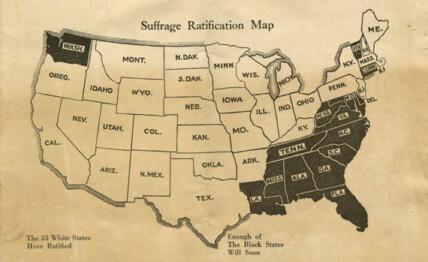

Frustrated by congressional inaction at the federal level, women’s rights advocates switched tactics and embarked on a grinding campaign to win women the right to vote state by state. This involved fighting to alter a patchwork of election laws with battles fought in statehouses across the country. Unfortunately, victories came slowly.

Despite setbacks, by 1917 over twenty states allowed women to cast ballots in at least some elections, with the American West being the most progressive area of the country. Most states there allowed women to vote in all elections, while the South proved the most resistant to enfranchising women.

During this period, most of the action in the fight for women’s rights happened on the state level, although there were still efforts to push national figures to endorse women’s right to vote. The most high profile activism happened at the White House, with protestors calling for President Woodrow Wilson to publicly come out in favor of women’s suffrage. President Wilson acknowledged this very sentiment in a speech before Congress, declaring his support for women’s suffrage in September 1918, asking, “we have made partners of the women in this war… Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

What may have caused a major shift in attitudes at the national level was the support of the U.S. war effort by most mainstream suffragists. Headed by Carrie Chapman Catt, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, America’s largest suffrage organization, provided public assistance to the Wilson Administration during World War I. The NAWSA’s support for the war made it harder to argue against women’s suffrage. How could one say that women, willing to support the fight for democracy abroad, did not deserve to participate in it at home.

Still, getting the amendment through Congress proved a major hurdle. Moments of high drama punctuated the final vote in the House of Representatives, with one congressman leaving the bedside of his dying wife at her urging to take part in the vote. The amendment barely passed the House on May 21, 1919, while the Senate rejected it twice before voting to approve the amendment in early June 1919. From there, it went on to the states for ratification.

ITEMS FROM THE COLLECTION