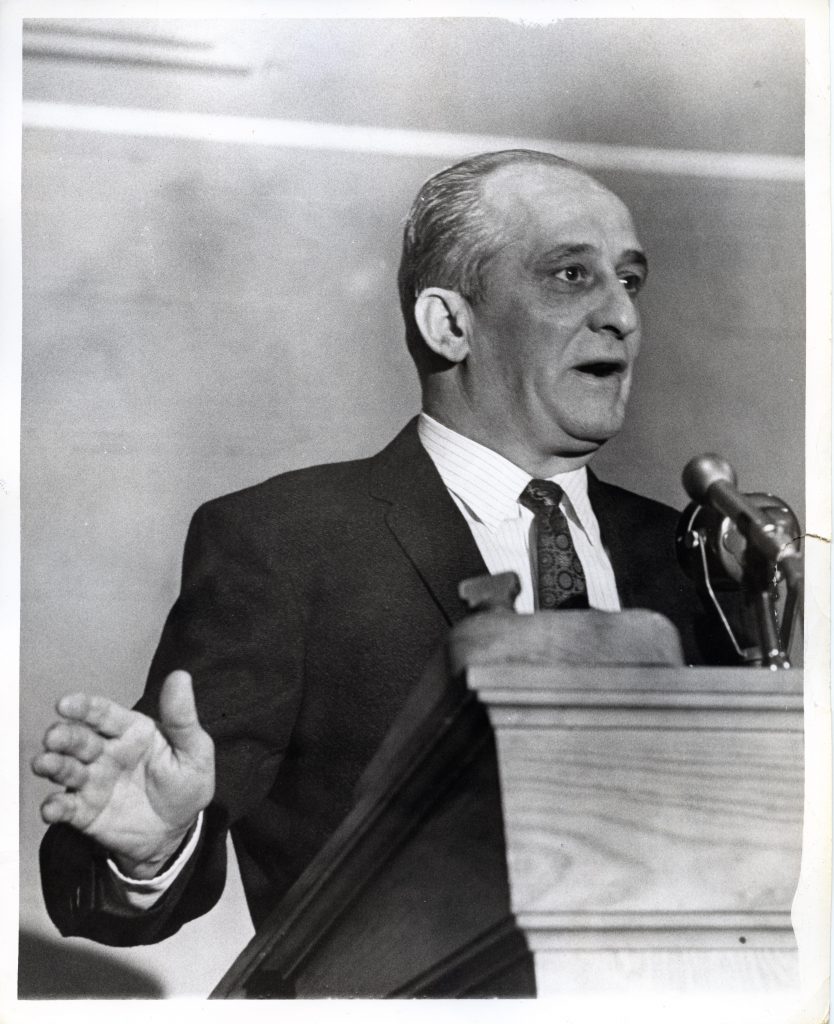

“AFSCME leader P.J. Ciampa”. Special Collections Dept., University Libraries, University of Memphis.

AFSCME national field director Peter J. (P.J.) Ciampa’s fulfilled a key role as a union negotiator in the early days of the strike.Pugnacious and hot-tempered, Ciampa, a former Pittsburgh steel worker rose in the ranks of the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations), ultimately becoming a regional director in the United Automobile Workers. Later he became the leading field organizer for the AFSCME. Ciampa heard about the decision for sanitation workers to strike soon after its commencement on February 12. Wise to the history of strikebreaking in the South, Ciampa exclaimed to T.O. Jones in a frantic phone call “Good God Almighty, I need a strike in Memphis like I need another hole in the head!” He soon flew back to Memphis to represent the national union in a state of fear, frustration, and anger. These feelings vanished, however, when he met the workers and witnessed their sincerity and resolve.

Ciampa’s pugilistic attitude polarized the public, infuriated the mayor, and endeared him to the workers. He, along with other local and national union figures, as well as representatives from the striking workers, met with Mayor Loeb and city government officials numerous times. In a meeting on February 13, Ciampa offered to get the striking workers back on the job if Loeb would recognize AFSCME as their bargaining agent; an offer Loeb flatly refused. Loeb couched his refusal by claiming that by striking, public employees broke the law, and he refused to negotiate with law-breakers. Ciampa replied by asking Loeb to name what crimes the workers committed, along with mentioning their poor working conditions as well as their poverty-level wages. At another heated meeting, Ciampa told Loeb that he “[had] not behaved like a public servant, but like a public dictator through the whole damn thing, and that’s tragic.” Loeb replied that he was sorry he felt that way but repeated that the union was breaking the law. At this point, Ciampa shook his finger at the mayor, raising his voice saying “You’re a liar when you say that. If I’m breaking the law, then take me into court. If I’m not breaking the law, then shut your big fat mouth.”

Loeb, who invited the press to these meetings under the auspices of “open government”, but primarily to shape public opinion, carefully kept calm in contrast to the brash Ciampa. The AFSCME, and Ciampa in particular, gained the perception of being Northern carpetbaggers coming to meddle in Memphis’ affairs, a trope as old as Reconstruction. “Ciampa Go Home” bumper stickers appeared soon after the start of the strike, and Jerry Wurf, the AFSCME president came to Memphis on February 18, more or less to take over the fraught negotiations with the city. Wurf soon found that Ciampa could not be fully blamed for the lack of progress, and Loeb’s obstinance and refusal to make any deals remained solid.

Drier, Peter. “Why He Was in Memphis.” The American Prospect, January 2007.

Honey, Michael K. Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign. New York : W.W. Norton and Company, 2007.

University of Minnesota. This is an account of the 1968 Sanitation Workers Strike… n.d.

Wayne State University. Wurf, King, Ciampa, Memphis. n.d.