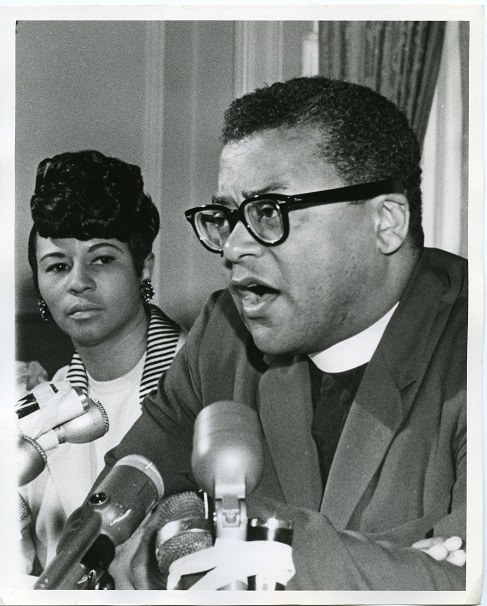

“James Lawson speaking to the Press.”Special Collections Dept., University Libraries, University of Memphis.

Memphians always directed the Sanitation Strike, often with great support from national figures. Reverend James Lawson, a Methodist minister, exemplifies Memphis leadership during this conflict. His nonviolent, yet confrontational style of protest inspired the numerous marches and sit-ins that occurred during this time. He could also draw from his deep well of professional and personal relationships, including a decades-long friendship with fellow pastor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Along with Dr. King, Reverend Lawson’s philosophical and personal influence place him at the apex of religious figures involved in the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike.

Born the son of a Methodist preacher in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, and raised in Massillon, Ohio, nonviolence inspired Lawson early in his life. As an undergraduate at Baldwin Wallace College, an Ohio Methodist institution, he delved into the philosophy of nonviolence and pacifism; drawing from thinkers such as Ghandi, Leo Tolstoy, and Reinhold Niebuhr. He joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) an antiracist, pacifist group. Here, he gained the acquaintance of A.J. Muste, a national leader in pacifist thought who in turn introduced Lawson to Bayard Rustin and James Farmer, both guiding figures to Martin Luther King, Jr. When Lawson received his draft card during the opening months of the Korean War, he simply returned it to the Selective Service Board without applying for any exemptions or deferments. He was arrested, convicted, and sent to federal prison for a five-year term for resisting the draft, however his term was reduced at first to three years, and finally he was released just prior to serving one year. While in prison, he became “very persuaded of the inability of a person to say that a man is bad.” In 1953, he traveled to India on a Methodist mission trip, where he continued his study of nonviolence.

After a while, he returned stateside and in 1957, while a student at Oberlin College, he met King who was on a speaking tour and they quickly formed a friendship that would last the remainder of King’s life. Lawson remarked to King that he ultimately wanted to work for political and social change in the South but he desired to wait for when the time would be the ripest for action. King replied, “This is the right time. Come now. We don’t have a person with your experience in nonviolence.” Lawson took this advice and took up the mantle as the FOR’s southern field secretary in Nashville, Tennessee. Concurrently, he matriculated at Vanderbilt Divinity School and became only the second African American admitted to that institution. He married Dorothy Wood, an activist in the National Council of Churches.

Lawson and King began to live parallel lives, as two well-travelled clergymen, both speaking to groups in the name of nonviolence and antiracism, and both heavily involving themselves in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC, of which King served as president). At King’s request, Lawson first chaired the SCLC’s direct-action committee, later becoming the director of nonviolent education. Lawson involved himself heavily in the freedom rides of Mississippi, where he briefly went to prison again. As Lawson grew in prominence within the Civil Rights Movement, he gained a reputation as an uncompromising, confrontational leader. In 1960, Vanderbilt Divinity School expelled Lawson for his actions, an action later reversed by the School when the dean and other members of faculty threatened to leave in protest. Lawson transferred in any case, to Boston University where he finished his master’s degree in theology. In 1962, he came to Memphis to become the pastor at Centenary United Methodist Church, the largest black Methodist church in the area, which included A.W. Willis among its congregation. While Lawson criticized the Memphis NAACP for being too indirect in their activism and overly comfortable with the Democratic Party establishment, he joined them to lead their education committee. He ran for school board and became a quiet force in Memphis.

When the sanitation workers went on strike in February 1968, Lawson involved himself soon after the inception. A constant figure in protest marches and sit-ins during February and March, he left a lasting mark through a speech he gave on February 24. He stated, “[f]or at the heart of racism is the idea that a man is not a man, that a person is not a person…You are human beings. You are men. You deserve dignity.” Concurrent with this speech, the slogan “I Am A Man” appeared on marchers’ placards. The phrase itself contains numerous historical precursors including the phrase “Am I not a man and a brother?” from the 1787 seal for the Society for the Abolition of Slavery. It also, as historian Michael Honey argues, serves as a rejoinder to the long-term racially discriminatory denial by whites of the adulthood of African-Americans. The short and simple choice of words cut to the heart of the matter: Are you, Mayor Loeb, going to deny the humanity of the marchers? And if not, then would you treat your fellow citizens and employees as servants with starvation wages? The effect of the signs is unquantifiable, yet “I Am a Man” boiled down the struggle to its essence.

Lawson kept King abreast on the Strike’s progress throughout. As March progressed, Lawson wanted his friend to come to Memphis and speak, giving the strikers a much-needed boost. King, fully engaged in planning for his Poor People’s Campaign agreed to come to divert attention to Memphis and start a previously booked tour of the Delta from there. On March 18 King flew to Memphis and spoke to well over 10,000 at the Mason Temple. Lawson led the march on King’s next return to Memphis on March 28. With King drawing huge crowds near the front the march, Lawson marshalled a bullhorn and attempted to bring calm to a rapidly deteriorating situation that included looting and violence. Lawson was omnipresent when King was in town. Lawson’s name was one few mentioned by King during his “Been to the Mountaintop” speech on April 3. In the immediate aftermath of King’s shooting, Lawson took the responsibility to record a message at WDIA, the premier radio station of black Memphis; such stood his influence and recognition within the community. Soon after the announcement of King’s death, Lawson and Benjamin L. Hooks received a police pass exempting them from curfew to go throughout the city calling for calm. At an event on April 7 called “Memphis Cares”, staged at Crump Stadium, Lawson warned that “Memphis will be known for a long time as the place where Martin Luther King was crucified…[but that to bring change there must be] a determination to work for transformations, real change, a move away from racism to genuine brotherhood.” On April 16, 1968, at city hall, the City Council met and adopted the memorandum of understanding, recognizing the union and ending the strike. Lawson was among the many in the crowd celebrating this hard fought, yet incredibly costly victory.

Lawson continued to push for labor recognition, workers’ rights, and black worker’s representation in unions in Memphis after the conclusion of the Sanitation Strike. In 1969 he supported black hospital workers who went on strike for numerous reasons, among them union recognition. While the strike failed, and Lawson was jailed, he continued to be known as a strong leader. He moved to Los Angeles, California and, while preaching there, continued his ministry for unionization of the poor and immigrant communities. He continued to speak against U.S. military interventionism as well as supporting gay and lesbian Methodists in Cleveland, Ohio.

Beifuss, Joan Turner. At The River I Stand. Memphis: St. Luke’s Press, 1985.

Honey, Michael K. Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign. New York : W.W. Norton and Company, 2007.

“Witness to Faith: James Lawson.”This Far by Faith. PBS: Public Broadcasting Service. (PBS.org)

“Martin Luther King, Jr.: I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” American Rhetoric. Top 100 Speeches.

Covington, Jimmy. “King Implored By Ministers to Come Here.” Commercial Appeal (Memphis, TN), Mar. 14, 1968.

“Am I not a man and a brother?” Broadside Collection, Prints & Photographs Online, Library of Congress.